Why Finding a 1990 Edition of Jessie Redmon Fauset's Plum Bun Might Change My Mind About Collecting Rare Books

Finding a Piece of Black Women's Literary History in a Local Black-Owned Book Store

I have no intention to be a rare book collector, which might be an odd statement given how much I like books and literary history. It might have more to do with the fact that I already collect books generally, as well as a number of other things like art supplies, journals and pens. I do have limits on the amount of memorabilia I let pile up even though I have an affinity for all types of physical media, including comic books, vinyl albums and DVDs. Books are one of the only things I allow myself free rein on, and still I have parameters.

Yesterday, I found the book that might make me reconsider my stance on collecting rare volumes.

I spent my Saturday afternoon driving out to The Printed Word bookshop in Portsmouth, Virginia. It’s a Black owned shop in Churchland, if you’re familiar with the 757. I’d had the intention to pay them a visit since I’d learned about them, which was recently considering they’ve had their shop set up for three years now.

When I came in, I was able to meet the owner, Tera Alston, who was warm and welcoming as she showed off the shop’s new and used book collections. From the vibe of other patrons of the shop, it’s clear she’s created an important space in the community. One patron came in with two children who immediately ran to hug the owner and then plopped down in the children’s book corner to occupy themselves. Clearly, this is routine for them and they’re comfortable in the space. Ms. Alston told me about the programs they run for children, like having local authors come read to them. The thought of a local space for young people’s literacy, outside of a school or library, warmed me.

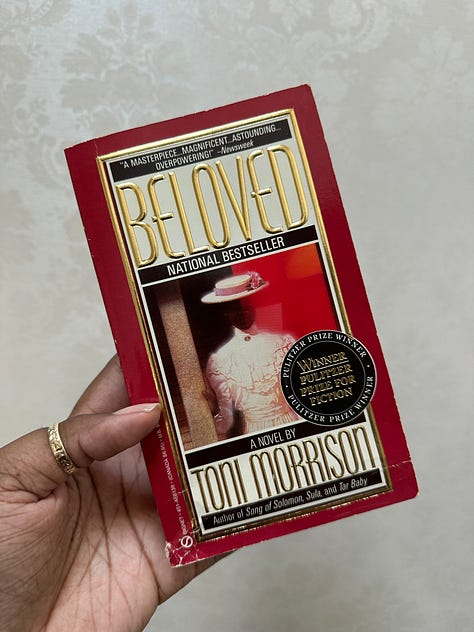

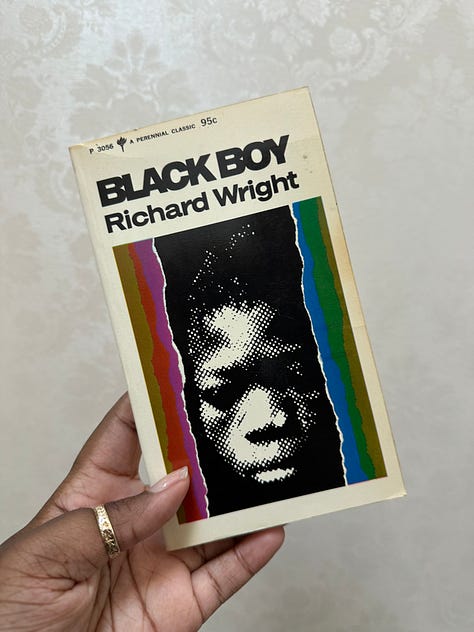

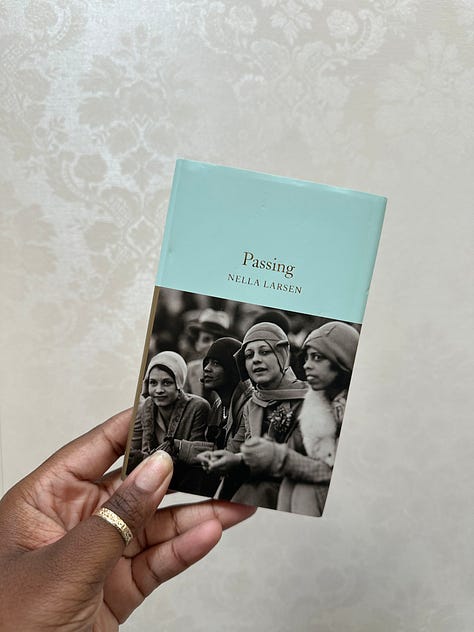

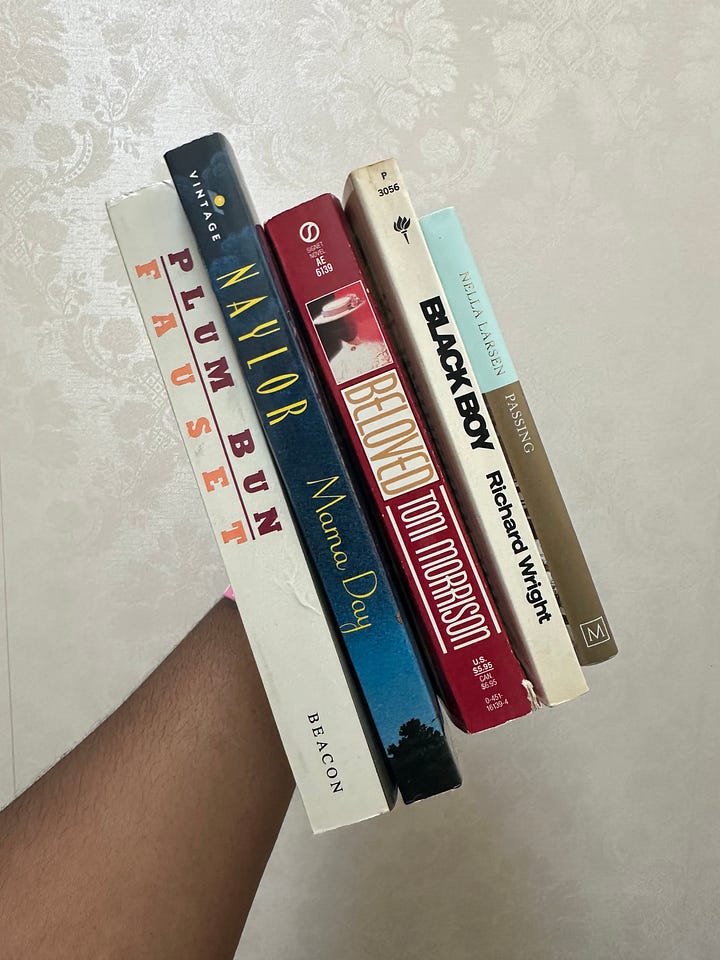

I learned a lot about the shop and Ms. Alston while I shopped. I had to stop myself from grabbing a bunch of titles from the new side; but they had so many of my favorite contemporary Black authors. Eventually, I scoured the used side, finding a few gems: a mass market paperback version of Beloved from the 1990s, an old cover of Richard Wright’s Black Boy I’d not seen before, and a sweet newer special edition of Nella Larsen’s Passing that likely was printed in around the release of the 2021 Netflix movie adaptation.

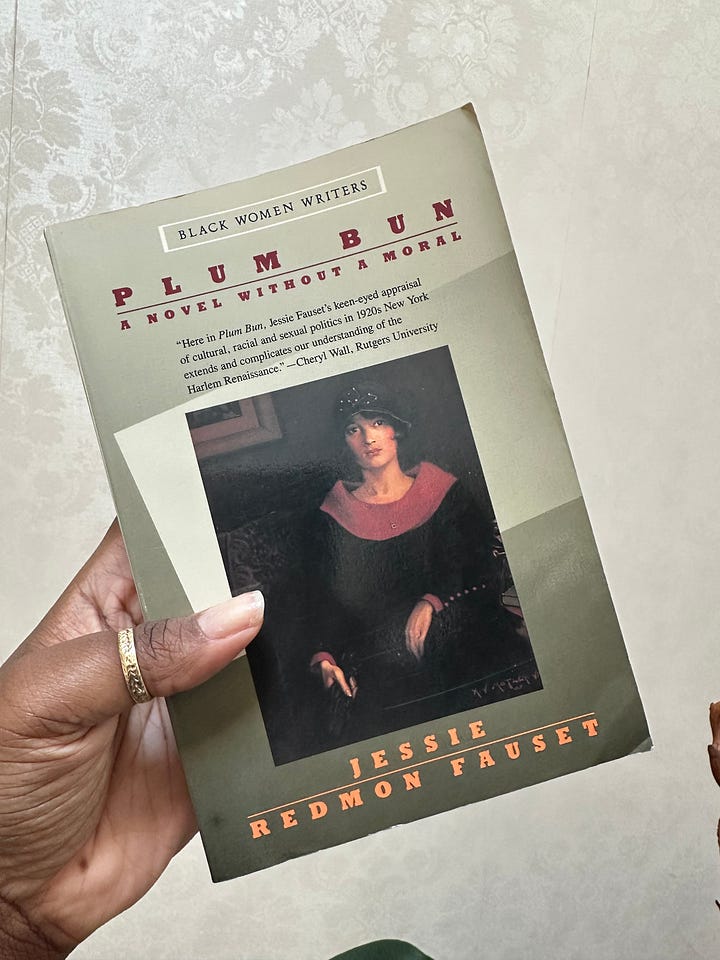

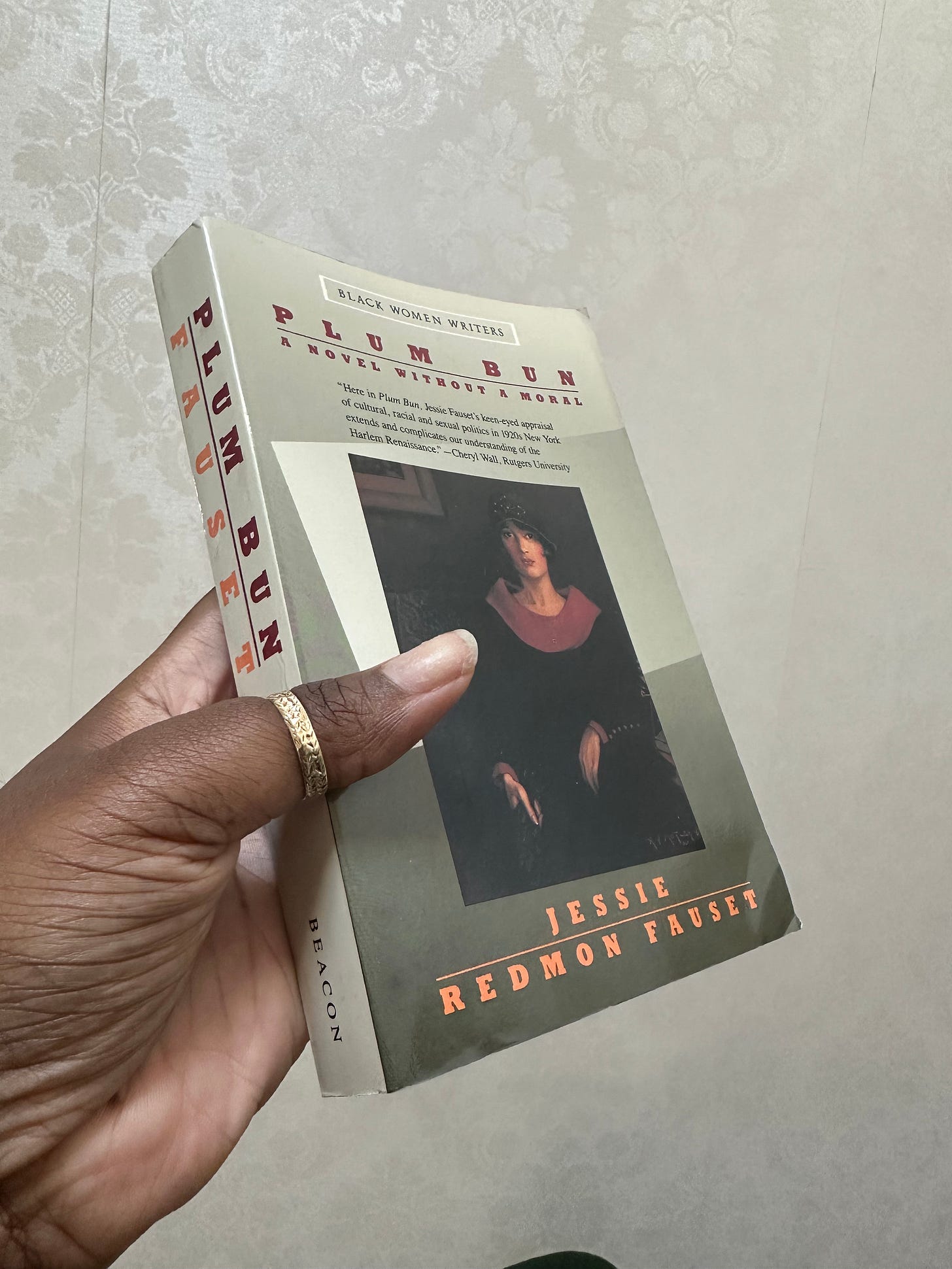

After probably an hour of chatting and searching, I was making a move to leave when I spotted a copy of Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset displayed proudly. Given the prominence of its position, I’m not sure how I missed it in my initial sweeps, but I literally stopped speaking mid-sentence when I saw it.

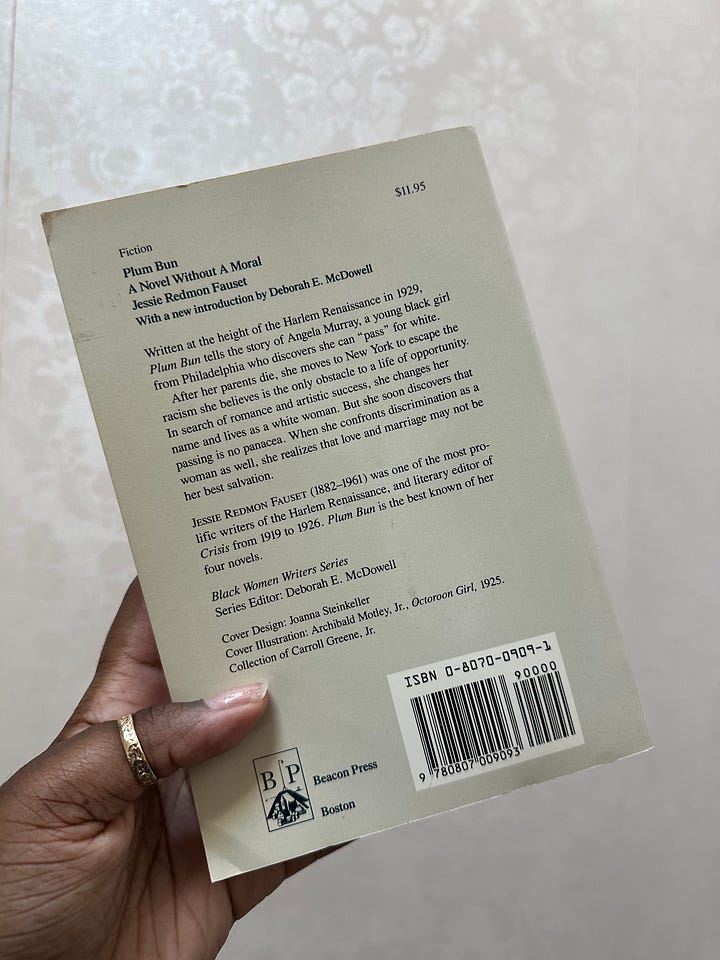

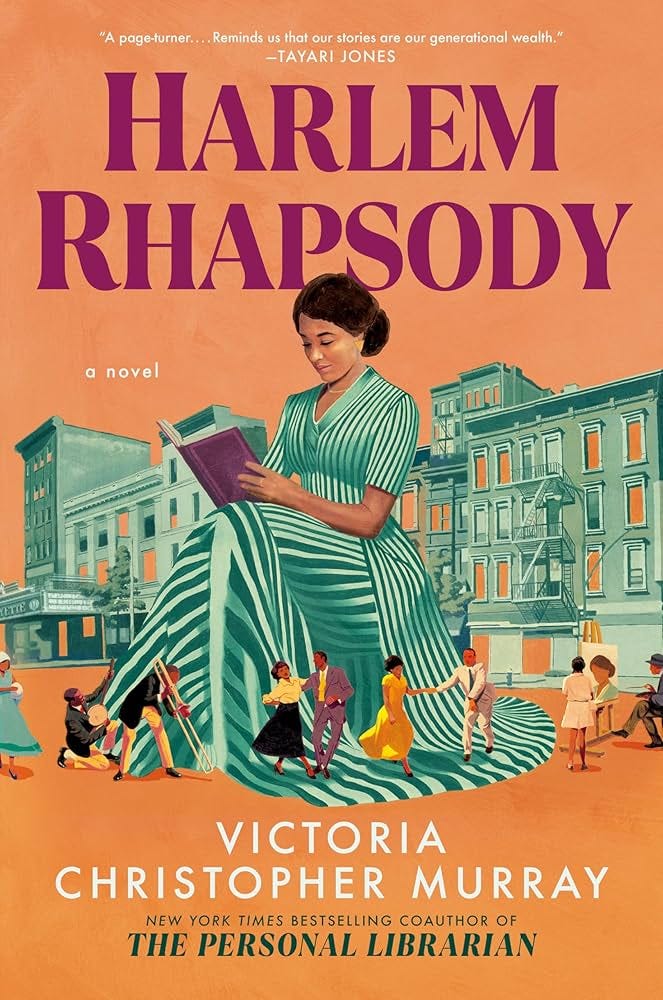

I knew it had to be quite an old edition, just based on what I knew about the book’s circulation since its publication in 1928. Fauset was a staple figure of the Harlem Renaissance, though her contributions were not as prominently known until fairly recently. Fauset became a hot topic in literary circles this year in the wake of the Victoria Christopher Murray’s historical fiction about her, Harlem Rhapsody.

Fauset was a novelist, publishing four novels, as well as a number of poems and essays. Plum Bun is likely her best known work. In addition to her literary output, Fauset was a dedicated teacher and diligent editor, making her one of the most prolific cultural workers of the Harlem Renaissance. She edited for both W. E. B. Du Bois’ The Crisis magazine and the short lived children’s magazine, The Brownies’ Book. Her sharp editorial eye helped her identify some of the most legendary voices of the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, and she fostered mentorships and friendships with a number of the movement’s writers and artists.

My personal interest in Fauset comes from what I view are similarities in background and thematic interests in our work. Fauset attended Cornell, loved French, and wrote about the particularities of a Black middle class. In many ways, she wrote what she knew, something I often aspire to do.1

Amid discussions of Fauset’s exemplary work record, the conversation that swirled around her this past year had a lot to do with her documented affair with (married) sociologist and writer W. E. B. Du Bois. To be honest, I have lots of thoughts about Black intellectual women’s pursuits of love, and have drafted an essay about it, but nothing I’m committed to sharing here at this moment. All this to say, our understandings of Fauset of have been interesting this year. Many of us went from not knowing her name at all to passing judgment about her life and work within the span of a few months.

My instinct is to grab the book. On further inspection, I realize its a Beacon edition and I actually do a dance in the store.

In the early 1980s, I believe 1983 but I can stand to be corrected, Dr. Deborah McDowell arrived in the University of Virginia English department, ready to teach. It was her intention to teach a Black Women Writers course, but she found that the novels she wanted to use were largely out of print. She was able to work with Beacon Press as an editor for Black Women Writers series to bring back fourteen titles into print. The series, which ran from 1985-1993, included reprinted books by Frances E. W. Harper, Gayl Jones, and Octavia Butler, among others.

Though Dr. McDowell was teaching at UVA while I was there as an undergrad (2012-2016), I unfortunately let myself be persuaded to not take her classes. Upperclassmen warned me off her, citing her courses were too difficult. Already having a hard time managing myself at the school, I decided not to add another stressor. I’m very fortunate that my paths ended up crossing with her anyway years later when I was assigned a retrospective for Shondaland on Ann Petry, a bestselling Black woman author from the first part of the twentieth century. Petry’s novel, The Street, was the first novel by a Black woman to sell one million copies. I was able to talk to McDowell for the piece and then later in conversation for an event with the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History on Petry. I’ve valued the digital relationship I have been been able to build with her over the years, always admiring of how much of a piece of living Black women’s history she is: she’ll sometimes share online a card or a note she saved from Toni Morrison or an old photo with Nikki Giovanni.

Though I’ve known about the series for a while, I’d never actually encountered one of the books from it in the wild. The volume I found was from that original series, reprinted in 1990. Given how much both Fauset and Dr. McDowell mean to me, I knew I was going home with the volume.

I was floating the whole rest of the day. I told as many of my friends who I thought would care and would listen about this book, and the backstory behind it.

Rare book collecting is not something I intend to take up. But if I were to do it…I think I would try to collect the rest of the books in this series. Lineage and legacies matter to me. I think often about where I fall in the family tree of Black women’s literary history. I change my mind often about where I think I go. The good news is: that’s not actually my problem to figure out. I’ll leave that to the historians and the critics.

For now, I will enjoy my little piece of Black women’s literary history that I found in a Black woman’s bookshop in Virginia, my home.

I like to think Love Requires Chocolate, my debut YA about a Black girl doing a study abroad in Paris because she’s obsessed with Josephine Baker, is in a Jessie Redmon Fauset tradition.

What a great article! I'm glad you were able to find this gem on our shelves!

I love this! My wife is a Portsmouth native and we are planning a joint beach/culture trip down from DC. We just did a run to Richmond for Frida!