"You Need A Record": Reading Toni at Random by Dana A. Williams

I tend toward generosity in my reading so I imagine folks familiar with my takes on media might think I’m overstating when I say Dana A. Williams’ book on Toni Morrison’s editorship is one of the most important of its kind.

Trust me, I’m not.

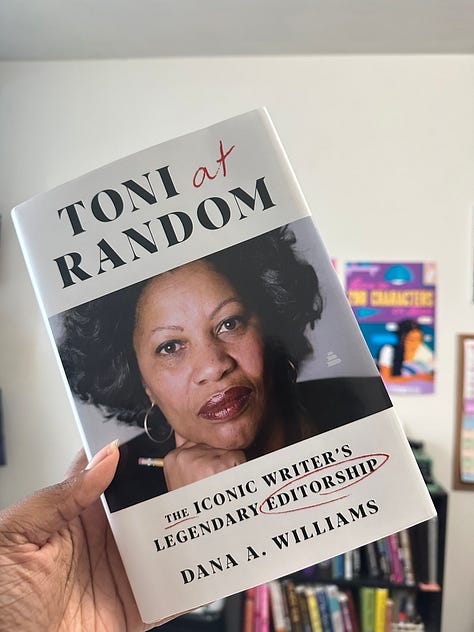

Howard African American literature professor Dana A. Williams’ Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship (Amistad, June 17, 2025) is ambitious—and delivers. The text is broken into sixteen chapters; the beginning few more biographical, setting the stage for the entrance of her marvelous relationships with a number of Black writers by chapter four. The subsequent chapters are roughly in chronological order, but largely grouped by author or theme (for example, Williams discusses all the poets on Morrison’s editorial list in one chapter). As an aside, Williams’ acknowledgments total 11 pages, the opening of which could have been a chapter in its own right detailing her personal interactions with Morrison and the inception of this book. If it is not in your habit to read acknowledgements, I recommend you read these!

The book balances showcasing the more creative or artistic work editing requires, with which more people tend to be familiar, alongside the “invisible” labor of editing. (p. 329) There are plenty of depictions in media of editors working alongside high strung authors, struggling to wrangle their words; Morrison had her share of authors that came with high demand and less willingness to enter into an editorial relationship. Interpersonal dynamics with writers came to a head as Morrison struggled to maintain a relationship with mentee Gayl Jones due to Jones’ representation and she chased down Muhammad Ali’s manuscript of The Greatest (1975)—years past when the pages were due to the company. Williams provides the reader with plenty of insight to the relationships through correspondence between Morrison and her writers.

But Williams recounts that Morrison spoke of her twelve years as an editor proudly, and based on the account, Morrison likely found many of her editorial relationships intellectually, and emotionally, fulfilling. Morrison had a strong relationship with Leon Forrest (There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden [1973]), and her friend Toni Cade Bambara (Gorilla, My Love [1972]). These two writers in particular were cited as two that entered into the editorial relationship with openness; Morrison enjoyed editing them as much as they enjoyed being edited.

The creative tact Morrison took with each writer depended largely on the writer, the project and their relationship to the words. She cites Bambara as having quite tight text, such that there was very little room to move things around—it was often good the way it was. Other writers, like Gayl Jones or Forrest, were open to inquiry about character, text, setting and the like.

As often as Williams regales the reader with personable anecdotes of high profile figures, such as inviting Angela Davis to stay with her and bringing her into the Random House offices to work, the author is sure to keep the industry workings at the forefront. Insight about how much authors were offered in advances, when payments were delivered, the size of initial print runs, debates about pricing volumes, notes about the tedious work Morrison put in on copy and design for book jackets, all of the correspondence Morrison penned to secure appropriate advertising placements, prove invaluable to understanding how the business of books. Based on her deft handling of the myriad responsibilities placed on an editor, Morrison proved to be as savvy a business woman as she was literary genius. (Who had any doubt?)

So often as I read, I found myself thinking, The more things change, the more things stay the same. Morrison’s hand wringing over having to price a book at $20 is reminiscent of the current grumbles at the prohibitive cost of hardcovers set between $30-32 (p. 285). Gayl Jones stress over how much public facing work is required of an author reminds me of the general distress of having to be an author on TikTok (p. 200). And of course, the irony of then Random House president Robert L. Bernstein declaring that “the day publishers refused to publish controversial books would be a bad day for democracy.” (p. 222) *Laughs in 2025*

Williams’ work is a text that I find valuable as a scholar/lover of Black literary history, a writer navigating the publishing industry, and an editor at a literary magazine. It is as instructive as it is a record. Documenting how others got through the industry makes it possible for the rest of us to figure out our way through. (Hint: much of it relying on each other to make it.)

Beyond that, it offers a new perspective on Toni Morrison that is absolutely needed. Black genius is often multi-faceted; most Black person working well in creative or intellectual industries has their hands in no less than three arenas. They do it all and they do it well, so much so it looks as easy as breathing—the true aesthetics of cool. Morrison’s work is flattened if we only consider her fiction. Between her novels, her essays, her teaching and her editorship, the image of her is rendered in even sharper relief and depth of her commitment to Black cultural work and community is on full display. Morrison had an unparalleled work ethic and eye for detail that she extended to the writers that she worked with; the way she loved you was through a rigorous grappling with your work. The expectation was that you would rise to the occasion.

It makes me think about genius, and who is afforded the comforts that come with being designated one. It might be tempting to think of Toni Morrison as a literary genius who spent the whole of her life mulling over the novels that are cornerstones of American literature. The truth of it is, Morrison spent more of her life grinding, spinning multiple plates at once, than she did just writing novels. I’m grateful for all that Morrison did, the legacy that she left, and I’m left wondering what might have happened if we had been able to acknowledge and support (in practical ways) her literary skill sooner. What if’s don’t serve much, I suppose. But we can always invoke sankofa—look back on what Morrison’s life and career tell us and use it as a guide post for moving forward.

And in the spirit of offering new perspectives on a singular genius, Williams also does such a beautiful job of injecting Morrison’s personality throughout. Her quips, her temper (though always honed with a well aimed barb), her reactions to her own mistakes, her love of her friends and her hobbies. I most enjoyed small moments of levity when Morrison tried to convince Angela Davis to visit Toni Cade Bambara, Bambara telling Morrison to relay that she had a popcorn popper as a selling point (p. 270). And when working on a book on New Orleans cuisine, Morrison’s skill in the kitchen came through in all her editorial suggestions (p. 314). Morrison was both a once-in-a-lifetime genius, and human. I value most the moments when these people are just that; Williams gives readers such a detailed portrait.

After leaving Toni at Random, I found myself thinking about other Black women writers and scholars who need a similar treatment. The first that came to mind was Dr. Deborah McDowell, professor emerita at the University of Virginia, who spearheaded the Black Women Writers series at Beacon Press in the mid 80s to the early 90s. Her desire to teach a course on Black women writers became frustrating when McDowell found most of the titles she wanted to assign were out of print. So she adapted the attitude so many of us Black women do and said, “I’ll do it myself.”

Those stories matter, too.

And as Toni Morrison so rightfully said: we need a record (p. 25).

And as Toni Morrison so rightfully expected: we must do the work.