Technomagic Girlhood

Exploring the intersections of the digital, fantasy and Black girls' creative practices

If you didn't know it, now-now you know

Moon Girl Magic! (Yeah I'm Magic!)

Thought you knew (Thought you knew, baby!)

Genius, inspiration overflow

Moon Girl Magic! (Moon Girl Magic!)

Thought you knew (Thought you knew, baby!)

When I first used “technomagic girlhood,” it was for my dissertation work. I was attempting to describe the something about Riri Williams as Ironheart that was not explicitly technological, but also fantastic. This was a Black girl who had used her very scientific know how and skill to engineer herself the ability to do a seemingly impossible feat: Riri Williams could fly.

That was years ago now. Before Dominique Thorne whooped her way across the sky in theaters across the world as Ironheart in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and before we got the truly joyous show that is Marvel’s Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur.

This is absolutely not to say I thought it first; what I am saying is: with more media where Black girls are making magic out of the technology and digital of their every day lives, I’ve been thinking about technomagic girlhood more and more.

The term has two points of origin for me: CaShawn Thompson’s conception or understanding of #BlackGirlsAreMagic, which later evolved into #BlackGirlMagic, and Dr. Moya Bailey’s digital alchemy. #BlackGirlMagic for Thompson was more about the magic we tend to make just by being, rather than any sort of celebration of accomplishment or status. The value was you, Black girl alive. And for digital alchemy, Dr. Bailey uses it describe the way that Black women turn everyday social media into extraordinary social justice magic. (Recently, she’s expanded on the term, breaking it down into types: generative digital alchemy and defensive digital alchemy. For more on that, see her book, Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance.)

The two of those ideas together helped me find a way to describe the ways that Black girls were making magic in digital spaces just by being. It’s the joy that Dr. Kyra Gaunt describes when Black girls play, creating dances on TikTok. It’s the way they build kinship practices in digital spaces, as Dr. Ashleigh Greene Wade describes in her research. Importantly, it’s in the way Black girls use every day digital and technological tools to craft their girlhoods, their young adulthoods, and all the selves that come after. (I think often of Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson’s article, “Alter Egos and Infinite Literacies, Part 3: How to Build a Real Girl in 3 Easy Steps,” in which she describes a lot of that self-making online. Hit me up if you want a copy; I keep one handy.)

Enter Marvel’s Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur.

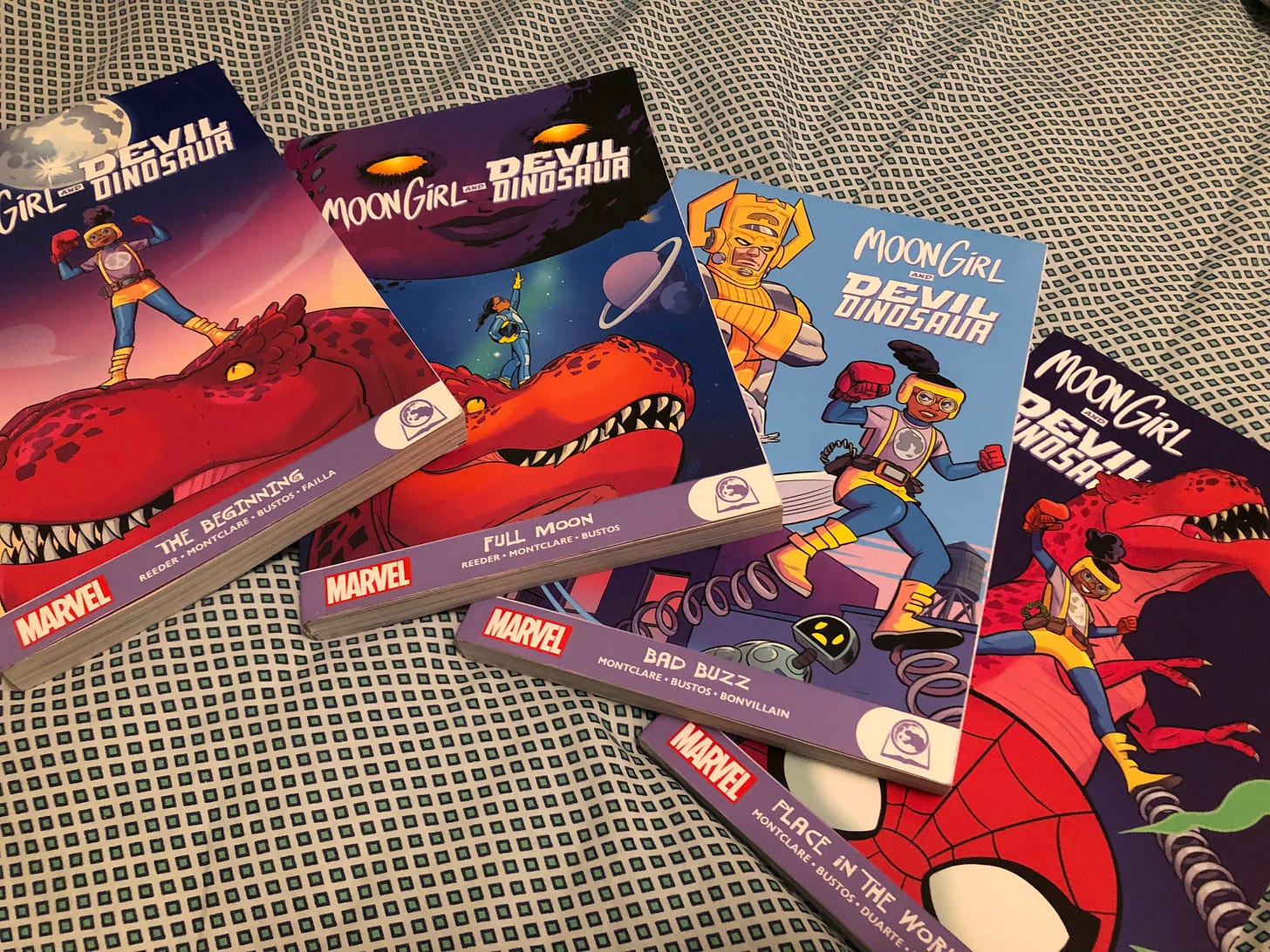

I love Lunella Lafayette, Marvel comics’ nine-year-old super genius. While I am certainly not the smartest person in the Marvel universe, nor do I have a cool red dinosaur, I do know something about being a smart Black girl in a public school and feeling like maybe you were meant for something more. (Comic Lunella is also very impatient and has very little tolerance for adults’ nonsense, something that I find extremely relatable.)

Naturally, I was excited for the show, which I knew would take big departures from the comics. The biggest departure, one that I find fascinating, is that as of now Luella’s defining characteristic is not necessarily the smartest person in the Marvel universe. The show treats her as a very bright, enthusiastic about science kid, but not as an isolated genius as she is in the comics. Show Lunella is surrounded by this fantastic web of family that we see in bits and pieces in the comics, and it’s often characterized by her parents’ worry about her being/feeling too different to fit in and Lunella’s general distance toward them. She also has friends, a whole community of the Lower East Side. This is of course the result of attempting to attract a younger audience—Lunella has to have interpersonal relationships and conflicts that are equally as compelling as the fantastic adventures.

But no matter the why, Lunella’s girlhood, both how she understands herself as an individual and who she is in community, is constructed with the use of technology in ways that are as mechanical as they are magical. Her catchphrase is “Moon Girl Magic” for a reason.

One, it’s (arguably) catchier than “I don’t have time for this foolishness!” (I, personally, love that catch phrase.) But two, it invites viewers to associate this girl with scientific/technological prowess with #BlackGirlMagic. The lyrics of the theme song also make it hard to know where the science ends and the magic begins: remember,“genius, inspiration overflow/Moon Girl Magic!”

It’s filled with potential and possibility, what magic Lunella is able to craft for herself. Her science, is a fact of life, and she is able to manipulate it to her wishes. It draws me back to “alchemy.” And while I primarily focus on the technomagic of Black girlhood, there’s space to think about Lunella’s Jewish and Latina best friend Casey’s technomagic girlhood as well, all that she is able to create from everyday pieces digital media—including her self making.

I have a longer piece in me about technomagic girlhood. It came out of the dissertation and I had the mind space to send it out to exactly one venue. When it was rejected, it sat in my archives. I don’t know if it’s a long CNF piece or a bigger research project.

What I do know is that I cry when I watch Dominique Thorne as teenage Riri Williams in Wakanda Forever soar through the sky and whoop with unrestrained glee. Every. Time.

Because she engineered herself the ability to fly. The self she is in the air is the freest there is. And that exemplifies technomagic girlhood to me.