If I discover that I love a writer, I stop at nothing until I have read most of their published work, which is how I ended up reading my fifth Hanif Abdurraqib book in six months.

Sometimes this project is next to impossible, as it is with Abdurraqib, because he has simply published so much in his career beyond the eight books he has written—four essay collections, three poetry collections and a children’s book about Aretha Franklin. When you have a mind that spins endlessly, the output keeps pace.

I keep digging deeper into his catalogue because I am astonished by how deep and wide ranging his connections go. By and large, writers want to show you their fruit, their harvest, the top part of the tree that is their work, the part that beautiful and stately. Abdurraqib shows you that—the lush language and poignant imagery—and the complicated rooted infrastructure below.

My love of hip hop is more inherited than personal. I love it because it reminds me of my dad, of rides in his Celica where he would go fast for five seconds so I would feel like I was flying. My mom was more of a gospel lady, so hip hop was for his solo rides, or the rare moments when I got him all to myself. The force of the acceleration and the bass vibration from the music against my back anchor split-second memories of bliss.

All this to say, I knew I would love Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest because I love Abdurraqib’s writing and I love anything that reminds me of my dad, not because I myself was rooted in deeply hip hop.

What surprised me was that I loved Go Ahead in the Rain because I recognized that this book was a physical manifestation of what it means to love something.

As I read, I collected individual songs that Abdurraqib mentions as he circles his love of the group into a playlist—things not limited to A Tribe Called Quest, or even hip hop more largely. All manner of artists and genres are necessary for the complete exploration of this one group, including surprising connections like The Beatles or Gladys Knight and the Pips.

By the time I was done, the playlist was over one hundred songs and nearly seven and a half hours long. I am confident I missed songs; I know this should be longer.

After I finished reading, I couldn’t shake the text. I doubled back. I wrote out every album Abdurraqib mentions by name. The list fills three entire pages.

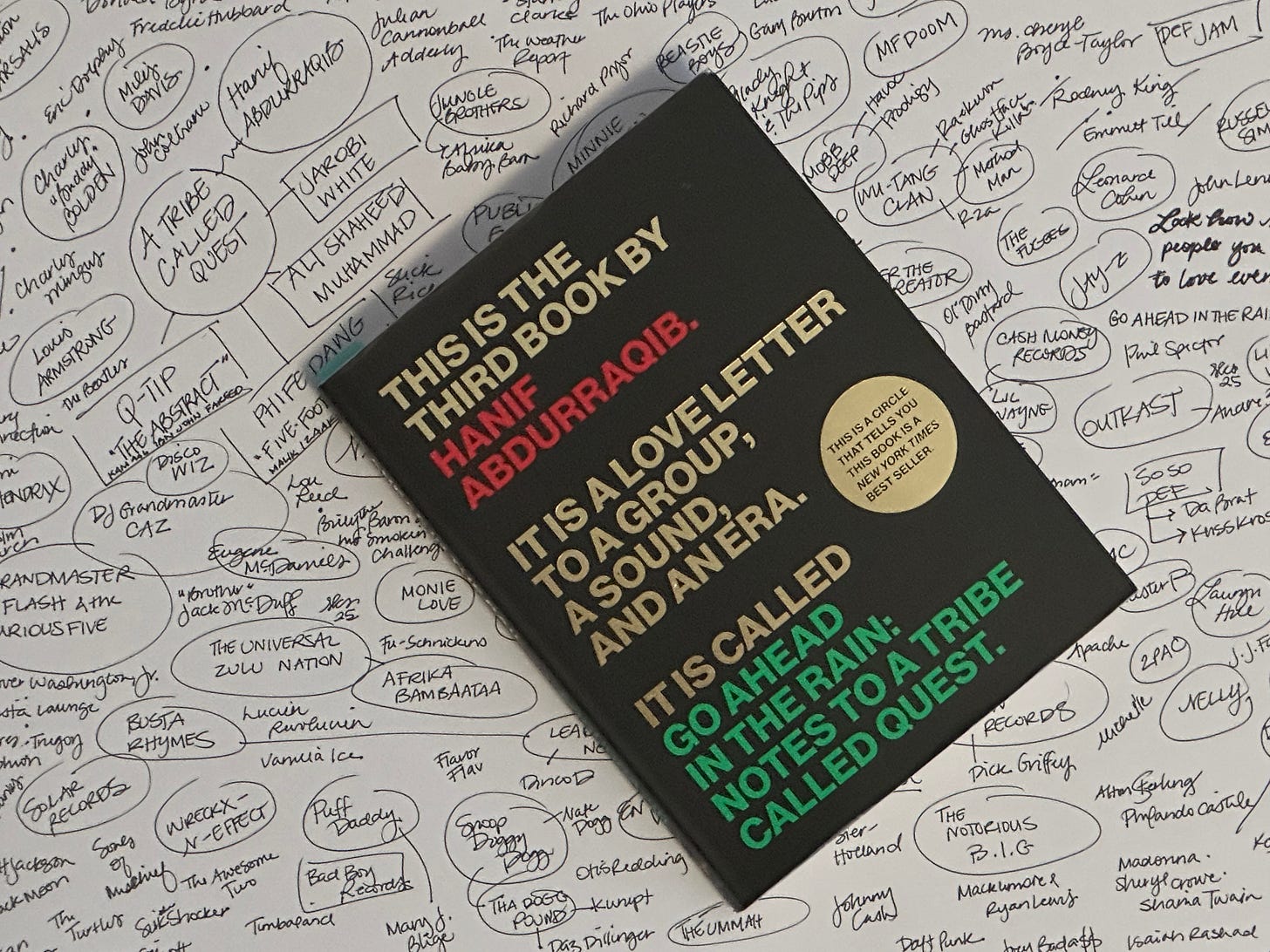

I went back again. This time, I wrote out most of the key players that are mentioned by hand—all the musicians, rappers, collectives, producers, their companies. It filled a 11 x 17 inch sheet of paper.

I knew before I embarked on Go Ahead in the Rain, I would need to prepare. For the week leading up to beginning to read, I listened to People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (1990), The Low End Theory (1991) and Midnight Marauders (1993) back to back while I went for walks. I knew a few songs well and had listened to the albums in college while taking “Sounds of Blackness” with Claudrena Harold at UVA, but hadn’t returned to them recently, knowing all that I know now.

My preparation was insufficient.

Once I got into the book, all I could do was witness someone doing a very diligent job of loving something for all of us to see.

Go Ahead in the Rain is in large part music history lesson, with a Who’s Who of major players and records from the 1990s, with an equally large mix of love letters to artists who were only doing the best the could with what they thought was right. It’s part eulogy for the fallen, an out stretched hand to a grieving mother, memorial for all that was and could have been. There are excellent sidebars about legacy Black magazines, particularly music ones like The Source, and the form of the documentary.

The fact that Abdurraqib can do all he does in roughly two hundred fairly small pages lets me know that he had waited all his life to write every word. There is no need to exaggerate. The love he offers around A Tribe Called Quest is robust.

I hear: Look how I love you. I love you enough to learn who made you, who you grew up with, and to whom you passed the mic. I must inspect everyone and everything you have ever loved because it created you.

Go Ahead in the Rain is crafted from a rigor fueled by love.

As a former academic, it is taboo to speak of love as if it matters in scholarship. But the work that I find the most rigorous, that demands the most of me, is the work that writers made because they loved something so deeply, their only desire was to explain it well. To get the story right.

I think love rigor fueled by love in the work of Toni Morrison, the woman whom I think of most after I leave a Abdurraqib text.

Don’t we owe it to ourselves to love deeply enough that we will labor in the hope we will render an image that reflects the love we have for the object of study?

It might also be taboo to speak of love as labor but it is. It is a choice to live in the roots of something. To tend to them.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be remembered as a writer who labored because she loved something?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be remember as someone who chose the work of loving every day?

This is so good. I've written a lot of cultural criticism, and I got to a point where I felt like I was just responding to other people's work instead of creating my own. But I think what you point out so brilliantly here is that Hanif's love for it, gives his OWN work form—thus allowing someone else to approach it with that same level of care.

Now I'm wondering if I'm giving up on criticism too easily.

Hanif’s mind is astounding. His heart is generous. And his sentences are simply unmatched. I’ve had the pleasure of hearing him read a handful of times — don’t pass up the chance if you get it.